The Salt Lake Tribune

October 23, 2001

Mountaineer Rescuers Make a Point by Sacrificing Summit

by JANET RAE BROOKS; THE SALT LAKE TRIBUNE

Tap Richards, Jason Tanguay, Andy Politz, & Dave Hahn

When President Bush called blind climber Erik Weihenmayer at 26,000 feet last spring on Mount Everest to wish him luck on his summit assault, he might also have put in a congratulatory call to some American heroes on the other side of the mountain. Tantalizingly close to the summit, Dave Hahn, Tap Richards and Jason Tanguay of the 2001 Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition gave up their own bid to scale the world's highest mountain to rescue five climbers stranded overnight at altitudes where only a handful have survived. While the Americans administered food, water, drugs and oxygen to the near-comatose climbers, other mountaineers continued past them on their way to the summit.

(See related photos »)

"We've shown it is possible to do a rescue up there," said expedition leader Eric Simonson. "But the corollary is that oxygen and horsepower can't be used for a summit bid, too. The bigger question is the obligation, this whole business of responsibility and accountability for one's decision-making."

Tanguay, who invested more than two months on Everest without reaching the summit, can't see drawing the line anywhere, if he can influence the outcome. "Even if they'd been grossly negligent, I still would have felt the need to help out," he said. "I couldn't imagine walking past anyone dying. It's no different than walking past someone dying in the street."

Tanguay and his climbing partners knew before they set out for the summit on May 24 that two climbers from another expedition — an American guide and his Guatemalan client — had spent the night on the Northeast Ridge after reaching the top at 2:30 p.m., past the accepted turnaround time. A record 89 people had scaled the summit that day.

Without the rescues, the climbers of the Mallory and Irvine expedition — all professional guides — were on track to reach the top as early as 7 a.m. The first to arrive on Everest that spring, they had developed into the best acclimatized team on the mountain. After weeks of route setting, establishing camps and high-altitude archeology, the chance to summit was a sweet reward. Their three previous summit attempts had been aborted for various reasons. With the mountain now overcrowded with climbers who had spent little time at altitude, they'd even considered calling off their final bid.

"It had the potential to end up like '96, [when 12 people died on Everest]," said Richards.

The three climbers left their high camp at 27,200 feet at 1 a.m. on a clear, windless night. After 3½ hours, they unexpectedly stumbled on three Russian climbers huddled by the landmark Mushroom Rock. Two were in serious trouble. The Americans spent almost an hour tending to them, before the Russians recovered enough to descend on their own.

Continuing up the ridge, they came upon Andy Lapkass and Jaime Vinals about 6:30 a.m., alive but unresponsive, with their jackets unzipped. While they squeezed gel into the mouths of the stricken climbers, helped them sip water and administered oxygen and dexamethasone, two summit-bound groups climbed by them. The first offered water; the second nothing. "They had other goals in mind, which we all did at the beginning of the day," said Richards.

Although they still hoped to revive the pair and continue to the summit — "the top from that point looks very close," said Tanguay — they soon realized Lapkass and Vinals would need help to get down. "It would have been a jaded summit climb if we'd gone on and had to walk past them on the way down without putting in that effort," Richards said. "It was the obvious thing to do."

There was no guarantee they would succeed. They struggled even to get the pair moving. "At the beginning, Andy was taking five steps and collapsing," said Richards. When Simonson radioed from Base Camp that they would have to leave Vinals if he couldn't walk, they held the radio to Vinals' ear to motivate him. Richards carried Lapkass' oxygen bottle to relieve him of the weight. Lapkass followed behind, leaning on Richards' shoulders and breathing from the tube from Richards' pack.

"It took us seven or eight hours to get down what had taken us four or five hours going up, and usually it takes half the time going down," said Tanguay. "There's some really tricky terrain between the First and Second Steps, and doing that with wobbly people put us in more danger than doing it by ourselves."

Finally, at the Mushroom Rock, where they'd found the Russians hours earlier, reinforcements took over the responsibility of constantly checking the pair's vital signs and maneuvering them down the mountain. Two years earlier, at 10:30 a.m., Richards had turned around at the same spot, fearing it was too late to reach the summit and return safely before dark.

Vinals' subsequent Web account of his summit triumph failed to mention the rescue. He returned to Guatemala to a hero's welcome. He later apologized to the Americans, explaining he had not written the dispatch.

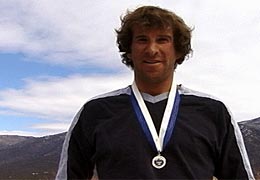

IMG guide Dave Hahn with the David A. Sowels medal he, Tap Richards, Jason Tanguay, and Andy Politz received for heroism in the 2001 rescue on Everest

The rescue — the highest ever on the Northeast Ridge — destroyed the established belief that climbers couldn't be saved at such altitudes unless they could walk on their own, said Everest historian and expedition member Jochen Hemmleb. "It's still high risk, and it's not certain, but it's possible," he said.

But only cooperative weather and the presence of a strong, experienced, well-equipped team, willing to sacrifice their own ambitions, kept tragedy at bay on May 24. Richards said he would make the same decision again, but feels jaded about returning to Everest. Tanguay still wants to prove he can reach the summit. "Because in my heart," he said, "I believe I could have."

He knows saving four lives — one Russian perished while descending — was more difficult and dangerous than bagging the summit. "But," he said, "no one gives you credit when you're 500 feet short."

Someone should.

—Jante Rae Brooks; The Salt Lake Tribune

Read More:- Read Dave Hahn's own account of the 2001 rescue »

- The rescue detailed in dispatches from the 2001 Everest Expedition »

- Related photos and David A. Sowles Award for heroism »

- See the London Times story of Dave Hahn's 2007 rescue on Everest »

© 2001 The Salt Lake Tribune. All rights reserved. Reproduced with the permission of Media NewsGroup, Inc. by NewsBank, Inc.