National Parks Conservation Association

Winter 2015 Issue

Under the Ice, Above the Clouds

A team of scientists explores the mysteries of Mount Rainier's Ice Caves

by Sandi Doughton

Bill Lokey planted his ice axe in the crumbly slope and scanned the cavern with his headlamp.

Counting all the ups and downs, he had climbed more than 15,000 feet to get here, past yawning crevasses and over cliffs where a single misstep could send a rope team tumbling. His party was pummeled by a lightning storm so ferocious it stood one woman's hair on end. Gale-force winds threatened to shred their tents.

But now, the grin on Lokey's face said it was worth it.

A ceiling of ice arched 40 feet overhead, glistening as the light danced across its scalloped surface. Steam hissed from volcanic vents called fumaroles, misting the air as it had more than four decades earlier when he first set foot in this otherworldly grotto.

Bigger than a ballroom, the chamber faded into darkness at either end.

"We called this the Coliseum," Lokey said, nodding in recognition—and awe.

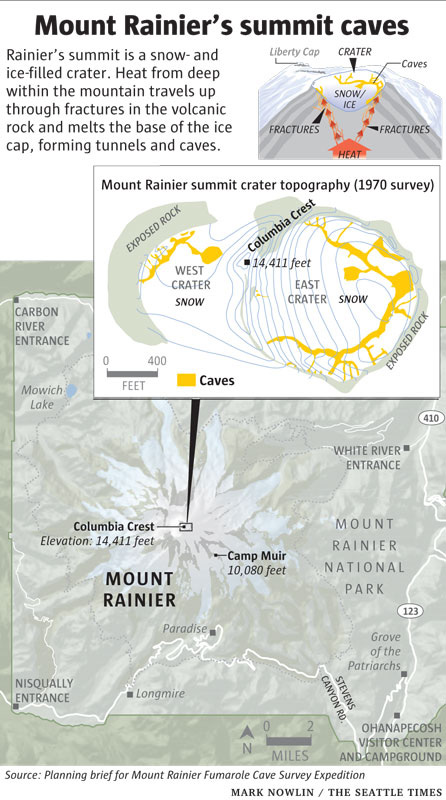

In the early 1970s, this was the biggest room he and a group of fellow adventurers encountered as they mapped and explored one of the Pacific Northwest's least known natural wonders: the labyrinth of ice caves at the 14,411-foot-high summit of Mount Rainier.

The caves form as heat rises from the volcano's depths and melts the base of the ice cap that fills Rainier's twin craters. More than 5,000 climbers trudge across those craters every year to tag the highest crest in the Cascade Mountains. Few have any inkling what lies beneath their feet.

The '70s-era map tallied more than a mile of passages in the main crater alone, with countless side channels left untracked. One chamber held a lake, which Lokey had named "Muriel" for his mother. He'd slithered headfirst down a chute dubbed the "Rabbit Hole," emerging to find an icicle as big around as an old-growth fir.

"To our knowledge, no comparable system... exists anywhere in the world," scientists wrote at the time—and no one has yet proved them wrong.

The adventure fired Lokey's imagination, and he's been itching to see the caves studied in more detail ever since. In the summer of 2014, he finally crossed paths with a team of experts who shared his passion.

Which explains why, at the age of 67, Lokey found himself back in the Coliseum.

With him was a biologist who studies microbes in environments so extreme they mimic other planets. A geologist joined the group to sample gases that could provide early warning if the volcano begins to stir. A professional photographer was on hand to improve on Lokey's grainy snapshots. A team of expert ice cavers came armed with mapping tools that didn't exist in the 1970s. And I tagged along to chronicle the adventure. The goal was to compile the most complete picture yet of the alien landscape and to tease out clues it might hold to the volcano's future and—perhaps—the origins of life.

Mount Rainier National Park officials welcomed the opportunity to learn more about a part of the mountain few rangers have ever visited. More accurate maps could help with search and rescue, says Roger Andrascik, the park's chief of natural and cultural resources. Monitoring changes in the caves over time could provide insights into the volcano's activity level and reveal more about the impacts of climate change as well.

Except for me, all the expedition members were experienced climbers. But that was no guarantee of success on a mountain that claims an average of four lives per year and foils nearly half those who attempt to reach its summit.

This would be Lokey's 40th trip to the top of the Northwest's iconic peak—and he very nearly didn't make it.

THE EARLIEST DESCRIPTION OF RAINIER'S summit caves comes from the first documented ascent. Gen. Hazard Stevens and Philemon Van Trump crested the crater late in the day on August 17, 1870. A bitter wind nearly swept them off the ridge. With nightfall approaching, the men were overjoyed to see steam jetting from the rocky rim. They took shelter in an opening carved under the snow by the heat and "passed a most miserable night, freezing on one side, and in a hot steam-sulphur bath on the other."

In 1954, Lou Whittaker and his twin brother, Jim, pioneers of Northwest mountaineering, ventured into the caves, but they turned back out of fear of toxic fumes. Lou returned in 1970 with a firefighter's breathing apparatus. He wormed through a small opening on the south side of the crater. "We called it threading the needle," he recalled.

For decades, the Whittakers led park visitors on tours of the Paradise ice caves, carved by water flowing under the Paradise glacier. Suffused with blue light, those caves vanished in the 1990s when the glacier melted back.

The summit caves were very different—dark and steamy with a hint of brimstone. But the air was breathable, Whittaker found.

During 1970s expeditions called Project Crater, Lokey and a cast of young mountaineers and scientists camped on the summit for weeks at a time. They used tape measures and compasses to size up passages, crunching the data with a slide rule. On the cave floors, they found dead birds, trash, and 19th-century climbing gear, proof that anything left on the summit would eventually work its way down. One cave contains the mangled wreckage of a Piper Cub airplane that crashed on the summit in 1990.

After the project, Lokey, who lives in Tacoma, built a career in emergency management, but his fascination with Rainier and its caves never diminished. In 1999, he guided a French volcanologist who paddled around Lake Muriel in an inflatable boat. But few scientists were eager to work in a place where blizzards strike year-round and the oxygen concentration is little more than half that at sea level.

The 2014 expedition team came equipped to deal with almost anything the mountain could throw at them. Those of us in Lokey's crew were loaded with winter camping gear, satellite phones, and food and fuel for more than a week. The cavers, led by U.S. Forest Service law enforcement agent Eddy Cartaya, lugged rescue equipment, gas monitors, and enough medical supplies to stock a field hospital.

When Lokey set off on a Monday morning in August, he carried 75 pounds on his back. At six-foot-two, with a bald pate and gear that dates to the Nixon Administration, he cut a conspicuous figure among young hikers sporting the latest parkas. Few of them could match Lokey's exuberance, though.

But by the time the 15-person team rendezvoused Monday afternoon at Camp Muir, a cluster of stone huts and outhouses two miles above sea level, Lokey and many others were exhausted by the seven-hour slog. A climbing ranger told them a storm was forecast to blow in Tuesday or Wednesday.

Our group had little choice but to take it slow. The plan was to summit early Wednesday—and hope the storm would hold off until then.

It didn't.

On Tuesday afternoon, soon after we pitched our tents at the head of a humpbacked ridge called Disappointment Cleaver, the sky darkened and began spitting pellets of snow.

Tent poles and metal stoves buzzed like angry bees. Zoe Harrold, a microbiologist from Montana State University, felt the electrically charged atmosphere lift her hair straight up.

With little shelter on the exposed ridge, we bolted for the lowest ground in sight. Huddled in a small saddle with the others, I shivered and cringed as lightning flashed through the clouds. Thunder echoed from all directions, and the wind blasted us with snow. It was an hour before the lightning abated enough that we could take refuge in our tents. The storm raged all night.

In the morning, the climbing route was obliterated by two feet of fresh snow. One member of the party picked up a forecast on his phone. More bad weather was on the way.

Traveling at a faster pace, Cartaya and his team had just reached the summit Tuesday when the storm boiled up.

"Big blue bolts were landing in the crater all around us," he told me later. "We grabbed our packs and ran for the nearest cave." Inside, water dripped from the ceiling. The fumaroles' exhalations warmed the air to 40 degrees, and Cartaya's meter registered no dangerous levels of hydrogen sulfide or other gases. The group made camp much as Stevens and Van Trump had done in 1870—but with the advantage of superior gear.

Nothing could keep the damp from seeping into their clothes, though, said Cartaya, who got hooked on ice caving when he moved to Bend, Oregon, to work for Deschutes National Forest. He and his team started mapping on Wednesday, marking way points and using laser range finders and inclinometers to measure distances and angles; special software will enable them to convert the data into three-dimensional images.

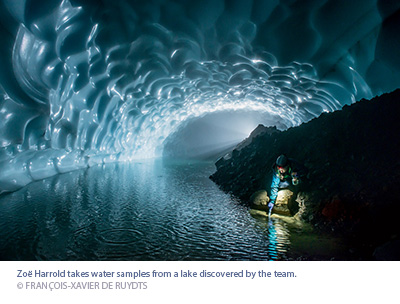

At the bottom of one vertiginous slope 200 feet below the surface, they discovered a lake that wasn't on previous maps. Cartaya called it Lake Adelie, because the azure water reminded him of the blue-eyed Adélie penguin.

But he could see right away that this expedition would just be a teaser. The cave network was much larger than the old maps reflected, with tantalizing passageways high overhead that would require ice-climbing gear to explore. Even as he jotted down dimensions, he started plotting a bigger expedition in 2015.

On Thursday, one of Cartaya's men woke with a rattle in his lungs. It was pulmonary edema, a life-threatening condition caused by elevation. The team cut their explorations short and descended that day—and the climber recovered fully. Meanwhile, Lokey and our group had retreated to Camp Muir to wait for better weather. At 2 a.m. Friday, we set out again. Thirteen hours later we reached the rim under sunny skies. Now it was the scientists' turn to go to work. Because the caves have been studied so little, it was mainly a mission of discovery.

"Guys, this is freaking awesome," United States Geological Survey (USGS) researcher Matt Bachmann exclaimed as he clamored through the labyrinth for the first time. He scooped up water samples from Lake Adelie for chemical analysis. "There might be something interesting, but we won't know until we look [at it back in the lab]," he said.

The fumaroles that sculpt the caves are of extreme interest, because they provide a window into the mountain's heart. Rainier's last major eruption was about a thousand years ago, but the volcano is far from dead. Its fumaroles, where temperatures reach a blistering 185°F, are evidence of a pool of magma miles underground. If that molten rock starts to migrate upward, the earliest indicator of a future eruption could be an increase in emissions of helium-3, a nonradioactive isotope enriched in the Earth's interior.

The USGS monitors helium at more accessible volcanoes but has no data from Rainier. Bachmann collected gas from seven fumaroles, using the end of his ice axe to nudge tiny copper tubes into the steaming vents. The results will establish a baseline against which to compare future measurements.

For microbiologist Zoe Harrold, the caves represent a once-in-a-lifetime chance to study an unexplored ecosystem. "What's really exciting is that we're basically starting from square one in an isolated, natural laboratory," she told me. Harrold specializes in extremophiles—microbes that flourish where most life withers. Rainier's summit caves present such a variety of withering conditions that Harrold had little doubt she would find some odd organisms.

She collected samples from the frigid lake and the superheated soil around fumaroles. She chipped chunks of ice from the cave walls, scraped up mineral deposits, and spooned mud into vials. What she learns about the microbial communities could help guide the search for extraterrestrial life and conditions that could harbor life elsewhere in the solar system. It could also yield insights into conditions on Earth when the first single-celled creatures arose. Weeks after the expedition, early results showed an abundance of genetic material in her samples, evidence of bacteria and other microorganisms. But it will require DNA sequencing to identify the players, and—if Harrold is lucky—six months or more to coax some of them to grow in her lab. Like Cartaya, she's making plans for a return trip.

Lokey reveled in the two days he spent on the summit helping the scientists and retracing his steps from 40 years ago. "It's just amazing to be here again," he told me before we headed down Sunday, seven days after our expedition started. But thrilled as he was to see the caves finally get serious attention, Lokey wasn't sure he would be back. This had been his toughest Rainier climb.

His knees ached, his shoulders throbbed, and his feet were rubbed raw. Worst of all, he feared he was simply too old. As he loaded his car in the Paradise parking lot, Lokey shook his head sadly. "I might be done with this mountain," he said.

Two weeks later, when the pain faded, he was immersed in planning for Cartaya's 2015 expedition.

But if he climbs again, Lokey said, someone else is going to carry the heavy stuff.

This article was a collaborative project between NPCA and The Seattle Times, where Sandi Doughton works as a science reporter. Francois-Xavier De Ruydts is an adventure photographer who lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, in Canada. He has captured images in deep caves and atop high mountains, but photographing both at the same time was a first.

© National Parks Conservation Association